Could lumpy metallic rocks in the deepest, darkest reaches of the ocean be making oxygen in the absence of sunlight?

While some researchers believe this theory, others dispute the assertion that what's known as "dark oxygen" is generated within the sunless depths of the ocean floor.

The discovery -- detailed last July in the journal Nature Geoscience -- called into question long-held assumptions about the origins of life on Earth, and sparked intense scientific debate.

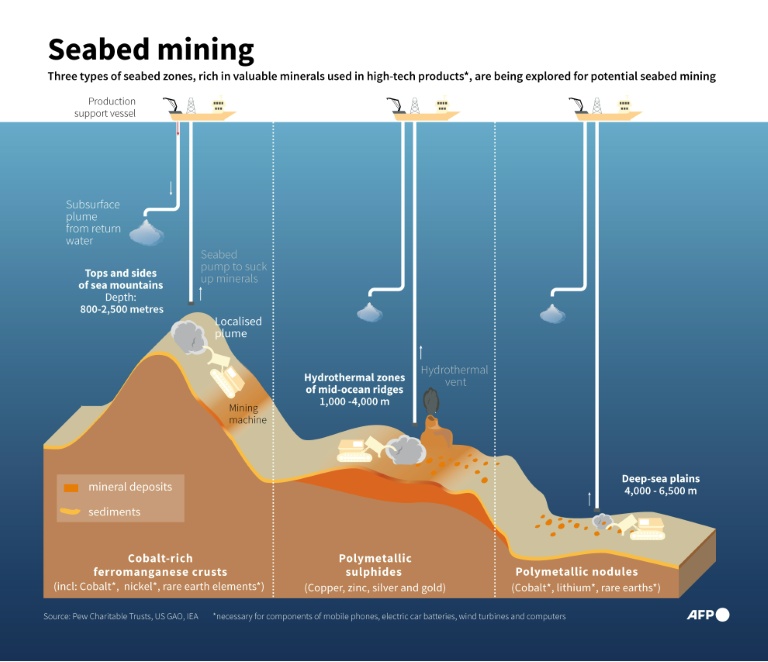

The findings were also consequential for mining companies eager to extract the precious metals contained within these polymetallic nodules.

Scientists have indicated that potato-sized nodules might generate sufficient electrical currents to separate seawater into hydrogen and oxygen through a process called electrolysis.

This raised questions about the widely accepted idea that life became feasible when creatures began generating oxygen through photosynthesis, a process dependent on sunlight, around 2.7 billion years ago.

"Deep-sea discovery calls into question the origins of life," the Scottish Association for Marine Science said in a press release to accompany the publication of the research.

- Delicate ecosystem -

Environmentalists said the presence of dark oxygen showed just how little is known about life at these extreme depths, and supported their case that deep-sea mining posed unacceptable ecological risks.

The environmental organization stated, 'Greenpeace has been advocating for years against the commencement of deep-sea mining in the Pacific because of the potential harm it could cause to the fragile ecosystems found in the depths of the ocean.'

This amazing finding highlights the critical nature of that appeal.

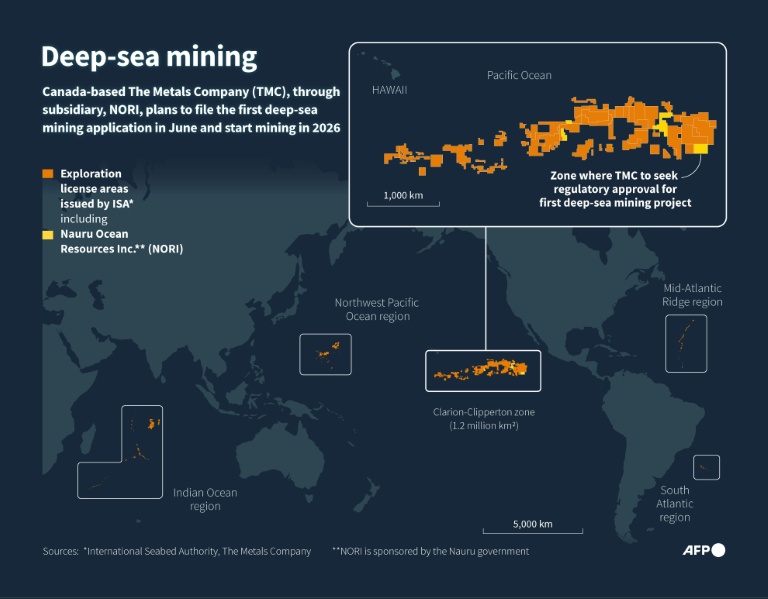

The finding occurred in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an extensive undersea area within the Pacific Ocean located between Mexico and Hawaii, which has become increasingly appealing to mining corporations.

Spread across the ocean floor at a depth of four kilometers (2.5 miles), these polymetallic nodules hold manganese, nickel, and cobalt—metals essential for manufacturing electric vehicle batteries and various low-carbon technologies.

The study leading to the dark oxygen finding received partial funding from The Metals Company, a Canadian deep-sea mining firm interested in evaluating the environmental effects of such activities.

It has strongly condemned the research conducted by marine ecologist Andrew Sweetman and his team, citing "methodological flaws" as the primary issue.

Michael Clarke, an environmental manager from The Metals Company, informed Pawonation.com that these findings can be better attributed to inadequate scientific methods and subpar research rather than some unprecedented occurrence.

- Scientific doubts -

Sweetman's findings proved explosive, with many in the scientific community expressing reservations or rejecting the conclusions.

Since July, five scholarly research articles disputing Sweetman's conclusions have been sent for evaluation and potential publication.

Matthias Haeckel, a biogeochemist from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany, stated, "He failed to provide concrete evidence supporting his observations and theories."

A multitude of queries persist following the release. Consequently, the scientific community must undertake comparable experiments and so verify or refute these findings.

Olivier Rouxel, a geochemistry researcher at Ifremer, the French national institute for ocean science and technology, told Pawonation.comthere was "absolutely no consensus on these results".

"Deep-sea sampling is always a challenge," he said, adding it was possible that the oxygen detected was "trapped air bubbles" in the measuring instruments.

He was also sceptical about deep-sea nodules, some tens of millions of years old, still producing enough electrical current when "batteries run out quickly".

"How is it possible to maintain the capacity to generate electrical current in a nodule that is itself extremely slow to form?" he asked.

Upon being reached out to by Pawonation.com, Sweetman mentioned that he was working on providing an official statement.

"Such exchanges are quite typical for scientific articles and they help advance the topic," he stated.

aag/np/fg/pjm

Post a Comment