In 2000, aMicrosoft exec delivered an enticing proposition to climber and physicist Chetan Nayak: Become part of their team at the Washington-based firm, and they could climb Mount Rainier together. build a quantum computer .

Within two years, he reached the summit of Washington's tallest mountain. However, the ascent towards developing a functional quantum device persists.

Almost every prominent technology company is striving to develop a functional quantum computer, aiming for significant advancements in areas like cryptography and pharmaceuticals. Unlike traditional bits, which are exclusively zero or one, quantum computing utilizes what’s called a qubit—capable of being both states simultaneously. This capability allows qubits to handle far greater amounts of data compared to current systems and execute specific computations much more rapidly.

Nayak heads a unit at Microsoft comprising hundreds of chemists, engineers, and mathematicians who have been working on developing a quantum computer for approximately two decades. This division, known as Station Q, pursues a strategy that is more daring and not as commonly endorsed compared to methods used by competitors like Alphabet's Google.

Should it prove successful, Microsoft might surge ahead of its competitors and debunk many skeptics within both the technology sector and the scientific community.

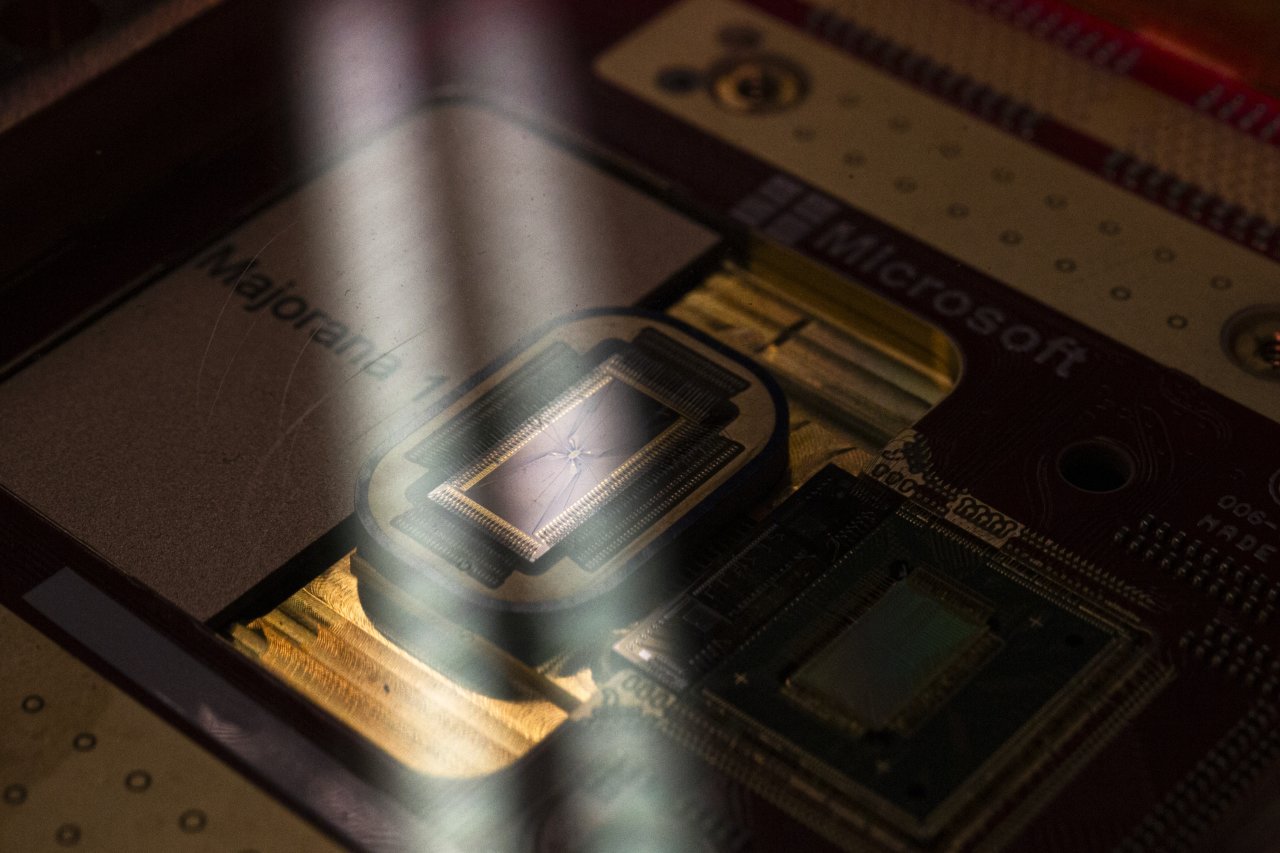

Last month, Microsoft announced that it had created a chip capable of generating a hard-to-find particle called a Majorana, which might serve as the foundation for a functional quantum computer. They claimed this advancement could hasten the development of such devices from decades to mere years.

While some physicists expressed doubt That Microsoft’s assertions might withstand their evaluation, CEO Satya Nadella seemed delighted to present something to the public. According to someone knowledgeable about the situation, Microsoft invests approximately $300 million each year into quantum research. This amount is relatively small when contrasted with their other investment areas. initiatives like artificial intelligence For more than twenty years,Microsoft’s expenditures on quantum initiatives have accumulated without much visible progress until recently.

Such progress is a stark change from seven years ago, when Nadella dismissed the company’s quantum efforts internally as research with no commercial potential, according to someone who viewed an email he sent at the time.

Nayak, who is 53 years old, characterizes his work in quantum research as a series of small advancements over time interspersed with breakthroughs that capture global interest, such as the announcement regarding Majorana particles. After these events, he returns to the daily routine.

"It's extremely difficult to convey this message differently without acknowledging that we're on the right path," he stated.

Nayak interacts with his team members at the facility in Santa Barbara, California, along with those based in Redmond and Europe, on a regular basis. All parties involved are acutely conscious that they are competing against each other. Meanwhile, Google also issued its own statement. quantum-computing advance employing a distinct method from Microsoft’s in December similar to what a firm named D-Wave Quantum did earlier this month.

Hooked on quantum

Nayak’s interest in quantum physics began during his time as a junior at Stuyvesant High School, a prestigious science-focused institution in Manhattan. This passion ignited when a teacher gifted him a book containing lectures by the renowned physicist Richard Feynman.

Quantum physics originated in the early 1900s and disrupts conventional notions of reality by suggesting that particles can be present in several locations at once and affect one another instantly over great distances.

Some executives at Microsoft and other tech companies have been predicting that a useful quantum computer powered by qubits would be commercially available in the next few years for at least a decade.

The problem has been reliability. All computer chips make errors, but on the ones in today’s PCs and smartphones, the error rates are minimal. On qubits, the slightest disturbance can cause them to make a cascading series of mistakes.

Under Nayak, Microsoft is tackling the problem with something called a topological superconductor. In it, a single electron is essentially spread across a tiny wire cooled to near absolute zero temperatures. Smearing that electron would form a Majorana particle, which has properties that can be used to make a qubit.

Microsoft contended in a paper Published in the scientific journal Nature last month, this study revealed that they had discovered a Majorana fermion and measured the information within it.

Qubit controversy

Experts in the field of quantum physics argue that the assertions made by Microsoft researchers about observing a Majorana particle are illusory.

Sergey Frolov, a quantum researcher from the University of Pittsburgh, claimed that "Chetan Nayak is overseeing a deceptive initiative at Microsoft." According to him, several inconsistencies found in the reported information could significantly alter the conclusions they assert.

Jason Zander, the Microsoft executive who oversees Station Q, said he was confident Nayak’s science would stand. The company is set to publish follow-ups to the Nature paper, which an independent set of researchers are reviewing. A Microsoft spokesman said the company holds itself to the highest ethical standards.

In 2021, two papers in Nature based on research partly funded by Microsoft about building Majorana particles were retracted because of questions about the validity of the research. Microsoft executives said the research wasn’t done by Station Q, but rather a Dutch lab to which the company had ties.

Now that Microsoft says it has shown off a Majorana, Nayak is focused on making the qubits even more reliable and adding more to the chip.

Nayak said he doesn’t want to still be working for Microsoft, trying to build a stable qubit chip, in his 70s. And he could finally put an end to the digs he gets from his three children, the oldest of whom was born around the time he joined Microsoft.

“Every time I say you haven’t cleaned your room yet, they say, ‘Well look, you haven’t built a quantum computer yet,’” Nayak said.

Post a Comment