Exceptional. This term encapsulates the talents of an unparalleled American performer from both theater and cinema, a monumental presence whose resonant voice brought galaxies crashing down as Darth Vader, and whose powerful performance as Troy Maxson in "Fences" reverberated through Broadway’s beams, alongside consistently mesmerizing roles such as the Moor of Venice, the boxer in “The Great White Hope,” and the hermit-like wise man in “Field of Dreams.”

Has there ever been a performance by James Earl Jones that didn't provide proof that giants roam the Earth?

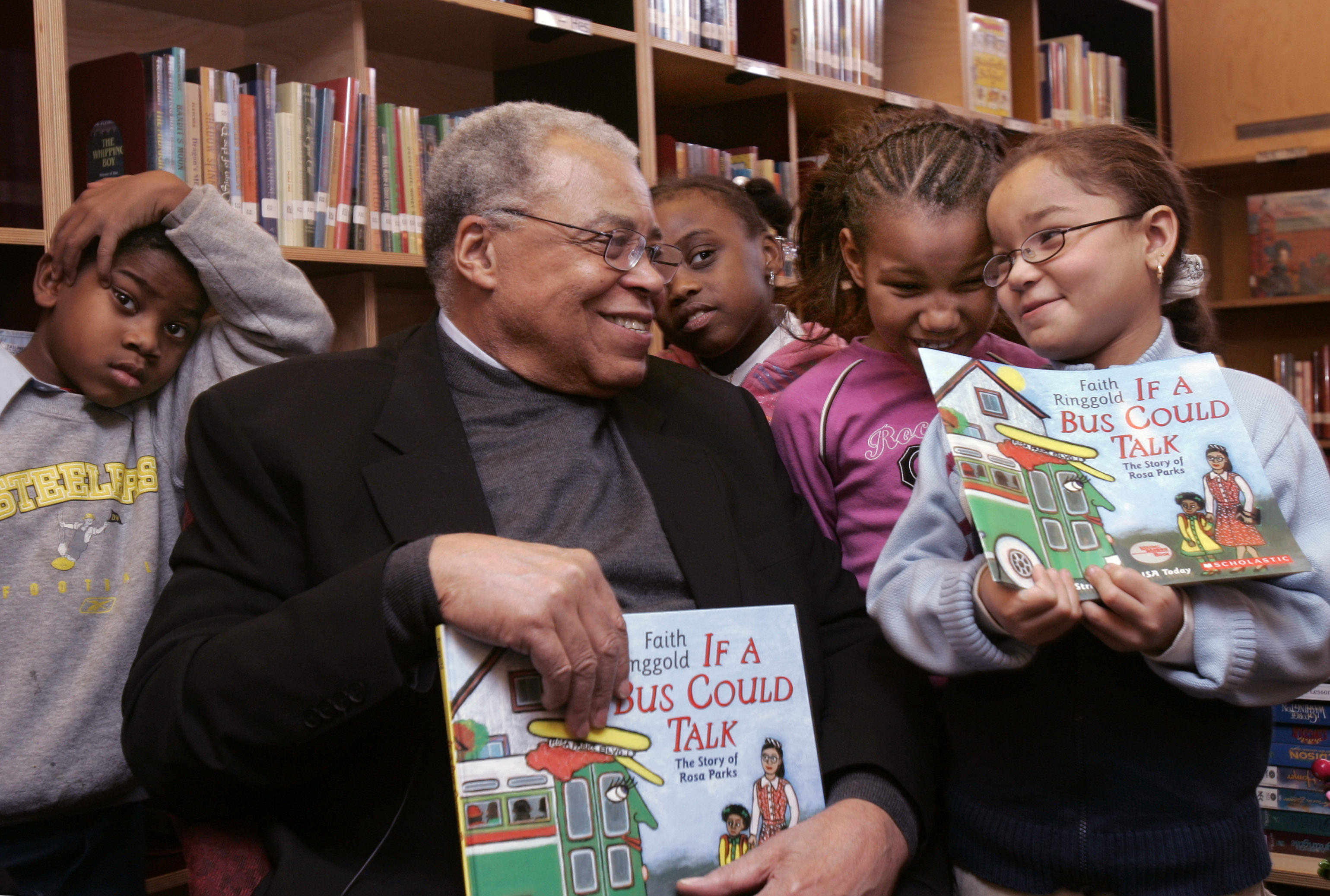

His innate ability expressed itself in such fulfilling ways over the years that Jones, who passed away on Monday at the age of 93, , became a go-to source for assignments that registered as consummately authoritative. Disney needed a regal sound for Mufasa, the reigning monarch of Pride Rock, in the original animated “The Lion King”? Ted Turner required the voice of a basso deity to intone his network’s lead-in and sign-off, “This is CNN”? Directors wanted a personality that radiated command, in films such as “Clear and Present Danger” and “The Hunt for Red October”? Whether it was a kingship or an admiralty, Jones seemed born to play it.

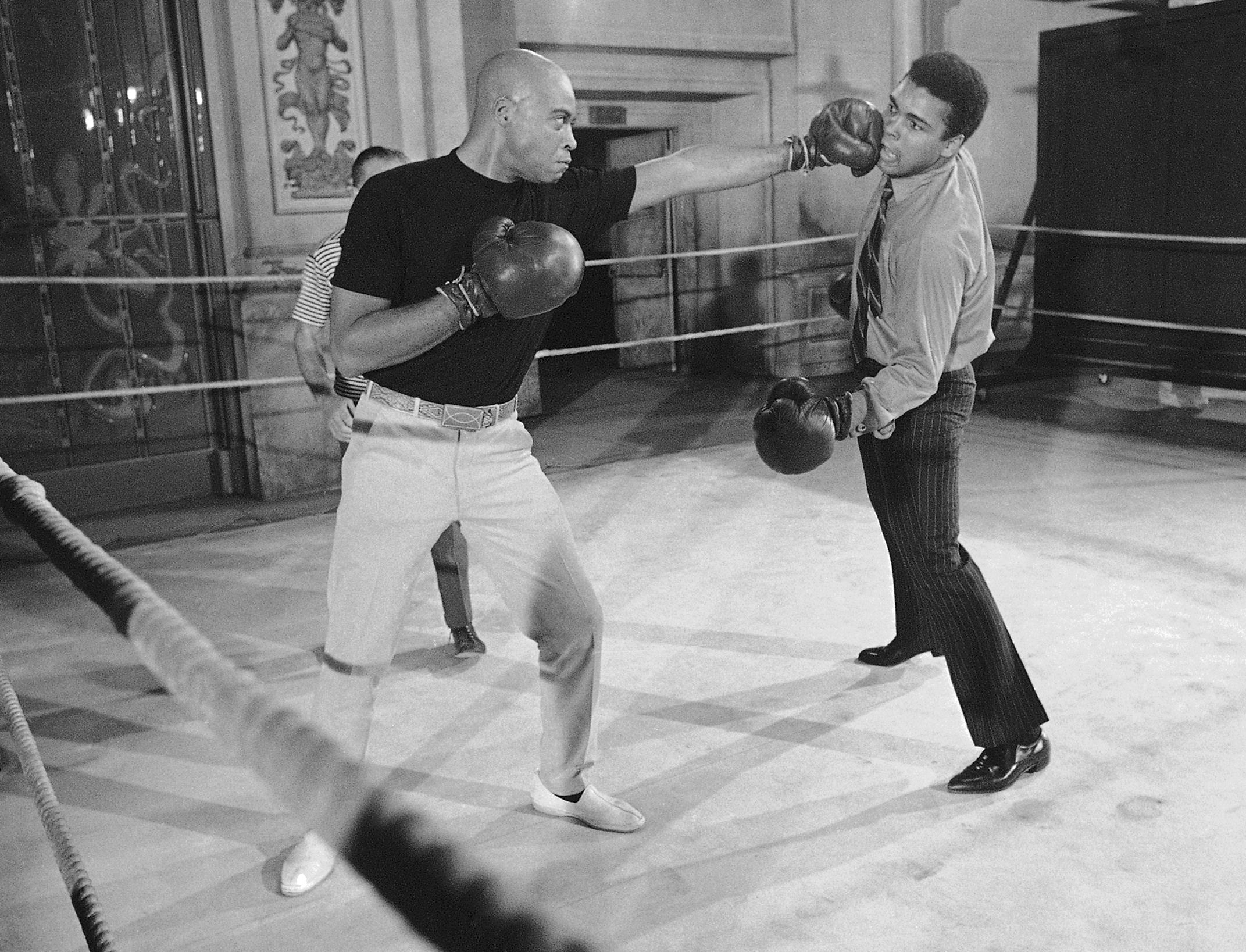

Of course, Jones's influence went far beyond what his vocal talents alone could unlock. He gained significant recognition in 1967 when he performed at Washington’s Arena Stage in the highly acclaimed world premiere of "The Great White Hope." This was Howard Sackler’s groundbreaking drama destined for Broadway and later awarded with a Pulitzer Prize. The story delves into the racial prejudices faced by Jack Johnson—known as Jack Jefferson in the script—who became the first African American boxer to hold the title of heavyweight champion.

Still, As he informed me when I saw him receive Kennedy Center Honors in 2002, Although he didn't see himself as a symbol of identity politics, preferring instead to think of himself simply as an actor who also happened to be Black, he found it amusing when fellow actors started mimicking his "Great White Hope" hairstyle by shaving their heads. He stated, while seated in a Georgetown hotel room, "I dislike the term 'race.' Being Black or having an ethnicity is straightforward; however, race creates divisions among people."

Perhaps it was the adversity he faced as a child in Mississippi and Michigan, raised by his maternal grandparents, that instilled in him a self-belief that rejected reflexive definition. He was, astonishingly given the arc of his life, a severe stutterer in childhood — practically mute, he said, until he was 14. He found his voice in high school, in the lyricism of literature. “It was through poetry I began to speak that other language, where the R’s were rounded: Longfellow, Shakespeare, Chaucer,” he recounted.

His refuge, it seemed, was in the cerebral universality of the writers he came to love. And so it is no surprise that the most captivating role of his career was conferred on him by that 20th century stage genius August Wilson. “Fences” is Wilson’s most beloved play, and Troy — the embittered sanitation man tormented by guilt and awash in disappointments — is the playwright’s most fully realized tragic hero.

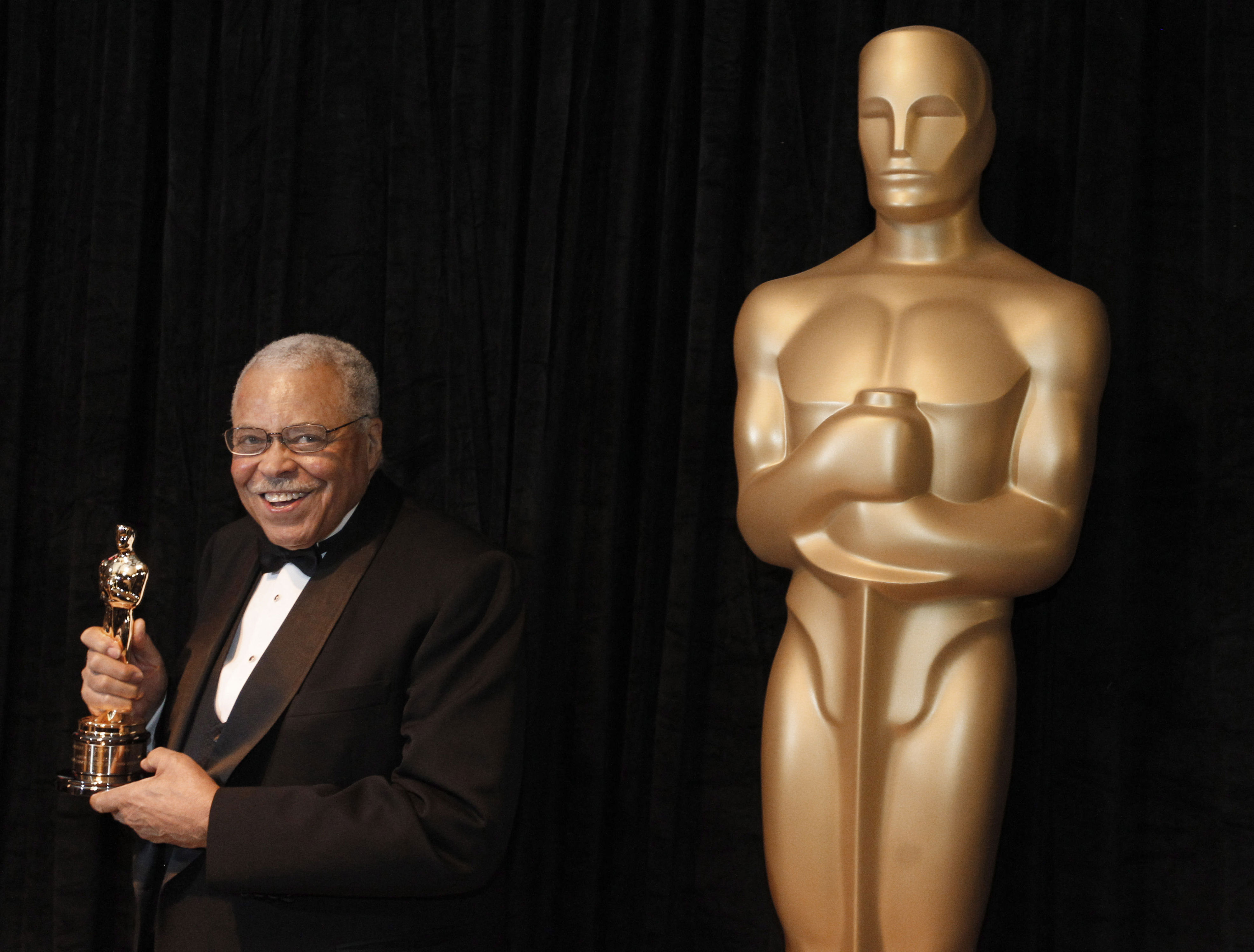

Jones played the hell out of the role, in the 1987 original Broadway production, directed by Lloyd Richards. The part earned Jones his second Tony Award for best actor — “The Great White Hope” was his first. Far more significantly, it affirmed the suppleness of Jones’s interpretive powers. I remember so vividly the climax, when, forced to confront the magnitude of his failures as a man and father, Troy raises a baseball bat to strike his son, Corey, played by Courtney B. Vance.

The situation was intolerable for Jones. He implored Wilson to clarify that Troy would never genuinely swing the bat at Corey. As Wilson hesitated, he collaborated with Richards to devise a physical signal indicating that Troy had no intention of following through and striking him. "At minimum," Jones shared with me, "I could exit the stage assured that I wouldn’t end up killing my own child."

The admission highlighted an actor who greatly committed to the emotional depth of a intricate character. However, he showed somewhat lesser dedication when it came to discussing contracts.Jones remembered that during the making of the initial Star Wars film —which went on to gross approximately— $775 million at the global box office — He received $7,000 for it. Furthermore, the Darth Vader recording session went on for just 2½ hours.

Twenty-one Broadway performances, along with numerous other theatrical productions, film roles, television appearances, and voice-over work populate an impressive resumé—a testament to six decades of contributions across various facets of American entertainment. Despite this illustrious career, meeting him felt endearingly unpretentious; even as he brought formidable characters to life until the very last moment, we bid farewell with warmth, culminating in his gentle request for a photo together.

“A Shakespearean stage director once told him, ‘Avoid getting consumed by the role of a king. Instead, portray a mere human,’ ” and this advice left an indelible mark on James Earl Jones.”

Post a Comment